How Really Post colonial are “Postcolonial” Studies In Nigeria?

$8.00

103rd Inaugural Lecture of University of Uyo.

Description

PREAMBLE

When I completed the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board’s (JAMB’s) form in 1979, language studies or English was not one of the courses I chose. Law was my first choice, and my first choice of institution was the University of Calabar; but it turned out that after we were admitted to constitute the first batch of students of the Faculty of Law, the University of Calabar realized that it was unable to commence its law programme that year; and so, those of us who had been admitted to the Faculty for

1979/1980 session were distributed to other faculties and departments. That was how I found myself in the Department of English and Literary Studies of the University of Calabar as a first-year student that year.

Whenever I look back now, I often wonder how well I would have fared both in life and as a lawyer if I had indeed followed that road which was not taken. Perhaps I would have done well, but today I have good reasons to thank God for directing my steps towards the study of English and Literary Studies, for the Holy Bible says in the book of Jeremiah, Chapter 10, verse 23: “O Lord, I know that the way of man is not in himself: it is not in man that walketh to direct his steps” (KJV).

The study of English, especially in former British colonies, is often like a secret kept in the open. In Nigeria, for example, everyone knows what is meant when one announces oneself as a student of English. The thinking is almost always that the person is studying such phenomena as English grammar (which includes both the written and spoken aspects of the language), and literature composed in English. Even within the university system, some persons are confused about the distinction between a

department of English and such other departments as Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, and or Foreign Languages. But those in these fields are aware that a department of English, especially in a post-independence country such as Nigeria where Britain had been the colonial master, is basically different from other related disciplines within the Arts and or the Humanities. Atypical

department of English is, hence, usually divided into two broad fields: language (which includes Stylistics) and literature. Literary criticism comes in, but it is often seen as an arbiter or middleperson between the writer and the society since the critic must relate and reconcile his/her interpretations and evaluation of the primary literary text, written or spoken, to and with the ideals and values of the

society in which the art is produced and whose material realties the art represents.

Within this world of study, my core area of specialization is General Stylistics and Literary Criticism. A general or linguistic stylistician typically sits at the boundary between language and literature, both fields of which he or she must master equally. He must be at ease with all the aspects of language study as well as with those of the study of literature. In addition, he or she must be a critic of literature because literature offers the richest pond in which he fishes, the site which he mines, and the field

which he ploughs in his scholarly engagements as a general stylistician. In other words, he must also

necessarily be a literary stylistician. In my case I have been something of a factotum, a sort of utility staff in the sense that, in addition to tilling in these subfields, I have also reasonably gone into creative writing, and have also tangentially crossed into such neighbouring fields as Linguistics, History and even further into African Cultural Studies. These incursions into neighbouring disciplines is

in tandem with the current trend in scholarship which entails that while one is still recognizing a particular area of specialization and maintaining fidelity to it, one should also cross-pollinate with other disciplines. Put differently, the trend now is in favour of multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches. Multidisciplinary research refers to a situation in which two or more scholars from different disciplines collaborate on a given single research project based on the research methods and approaches of the different disciplines but aiming at producing a common result. In most cases the outcome is usually more revealing and rewarding than what would have been the case if the

research had been done from the perspective of a single discipline. Multidisciplinary or inter-disciplinary research, indeed, widens the scope of knowledge and shows the interconnectedness of disciplines that would have been deemed to be far apart. Medicine, for instance, has been commonly cross-bred with music and poetry, and the results have often been wonderful. Trans-disciplinary

research entails a situation in which scholars from different disciplines harmonise the tools, techniques or research methodologies of their different areas of specialization but with the same outcome in view. In my scholarship I have often indulged in this kind of research efforts, which means that I have often applied the methods in my area of specialization to research in neighbouring disciplines.

This inaugural lecture is, hence, a brief account of my humble contributions to the broad, two-pronged fields of English and literature, each of which, in turn, divides into quite a number of subfields. I have also made some tangential incursions into the study of history, particularly in the area of slavery. Linguistics, unlike English or any particular language, pertains to the study of the nature and

patterns of natural or human language as an abstraction and with a high degree of predictable scientific precision. That is why in some universities, particularly outside our shores, degrees in linguistics are classified under the Sciences rather than under the Arts. Linguists draw their illustrations from all manner of human language; this is why in Nigeria linguistics is commonly conflated with the

study of Nigerian languages, as we have in the University of Uyo, for example. In sum, this inaugural lecture embeds my teaching and research experiences in language, linguistics, literature, literary criticism, culture, history, and education, all being fields in which I have made modest contributions in the 40 or so seasons that I have ploughed within the vineyard of the Nigerian university system.

In most of these studies, my thrust has been on the condition of Africa, particularly Nigeria as a former

British colony and its stillbirth following the ersatz independence of October 1, 1960. This ideological

preoccupation underscores the ubiquity of the terms “colonial/colonialism”, post-colonial/postcolonial/postcolonialism,” and “neo-colonial/neocolonialism” in much of this presentation, just as they exist in much of the work I have done within this period and from the different fields and perspectives. It is also the justification for my choosing the term “postcolonial” as the overarching concept for the lecture since much of what I have done can find space within the orbit of this term or its close neighbours such as “colonialism”, “post-colonialism” (with the hyphen), and “neocolonialism”. The lecture is thus organised around the following nine broad subheads:

(A) Key Concepts; (B) Language; (C) Linguistics; (D) Literature; (E) Literary Criticism; (F) Culture; (G)

History; (H) Education and (I) Conclusion and Recommendations. We begin with a brief explication of

some of its key concepts.

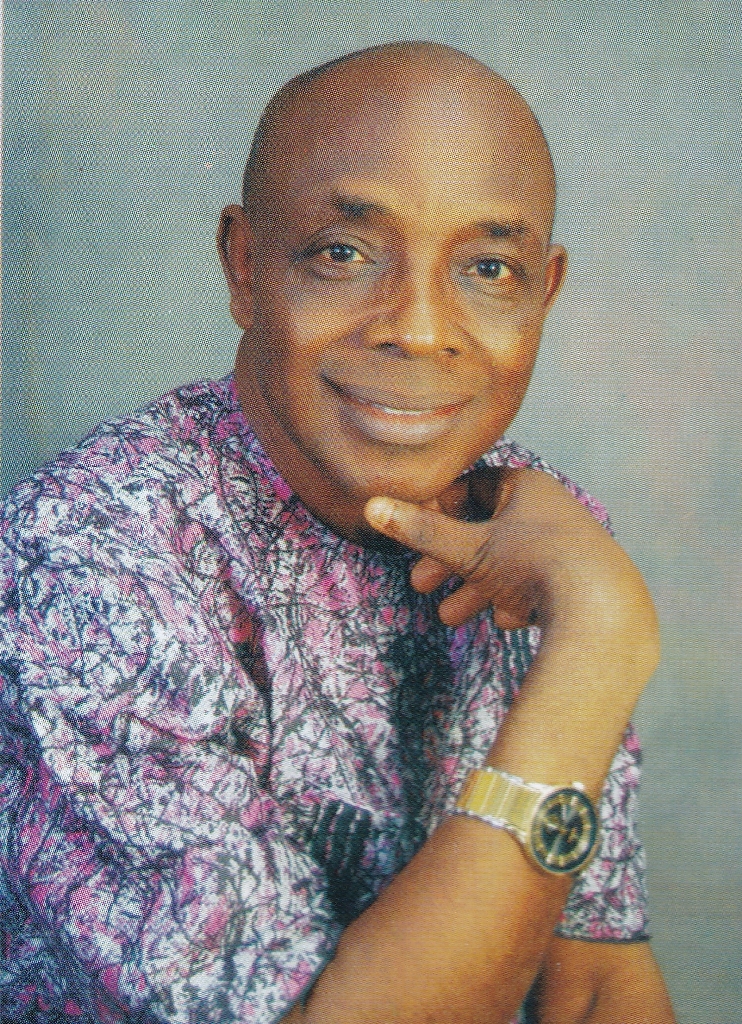

Prof. Joseph Ushie

Joseph Akawu Ushie is a Professor of General Stylistics and Literary criticism at University of Uyo, Akwa Ibom State Nigeria.

He is the current Vice-Dean, Postgraduate School, University of Uyo, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. He was born at Akorshi, Bendi, the hilly Obanliku Local Government Area (which houses Nigeria’s foremost tourist attraction, the Obudu Cattle Ranch) of Cross River State, and he attended St. Peter’s Primary School, Bendi, Government Secondary School, Obudu, and the University of Calabar, Calabar, where he studied English and Literary studies, and was the Secretary-General, Student Union Government in 1980-81 session. He subsequently obtained the M. A. (1988) and PhD (2001) in English from Nigeria’s premier university, the University of Ibadan. Professor Ushie had served as Head, Department of English, and on several boards and committees in the University of Uyo. He had also been Chairman, Association of Nigerian Authors, Akwa Ibom State Chapter, Judge, ANA national literary competitions (2009 – 2010), Juror of the Canada-based International Poetry Competition (2017) and a Co-Editor, Montreal 2017 Global Poetry Anthology.

Questions and Answers

You are not logged in